A Brief History

Brasenose College Boat Club is one of the oldest boat clubs in the world, having beaten Jesus College Boat Club in the first modern rowing race, held at Oxford in 1815. The 1815 contest is the first recorded race between rowing clubs anywhere in the world. To this day, Brasenose and Jesus Men’s 1st VIIIs compete in a race on the Isis for the 1815 Challenge Plate. Brasenose is the current holder, having won by several lengths in 2013.

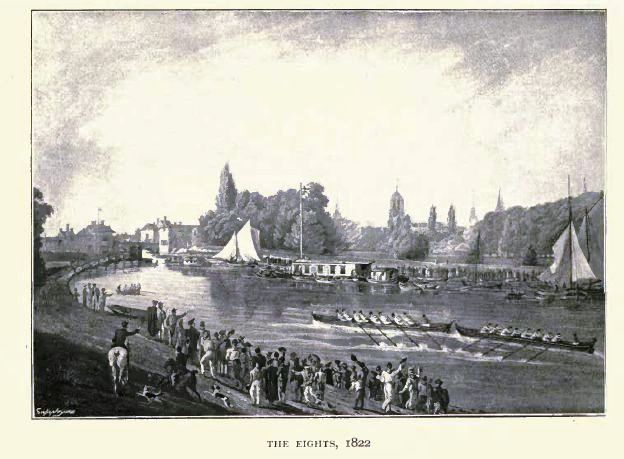

In 1822, crews from Jesus and Brasenose raced each other to become Head of the River. One Brasenose rower caught a crab, slowing the boat. The Brasenose boat was bumped by the Jesus boat, but then began to row again and finished ahead. As there were no definite rules in those days, both the Jesus and Brasenose men competed over which college’s flag should be hoisted to denote the Headship. One of the Brasenose crew ended the dispute by saying “Quot homines tot sententiae, different men have different opinions, some like leeks and some like onions”, referring to the leek emblem on the Jesus oars, and it was agreed to row the race again. The Brasenose crew won the rematch, and the incident has been said to be shown in an 1822 picture titled “The Eights”, the earliest depiction of an eights race at Oxford, painted by John Thomas Serres (Marine Painter to George IV).

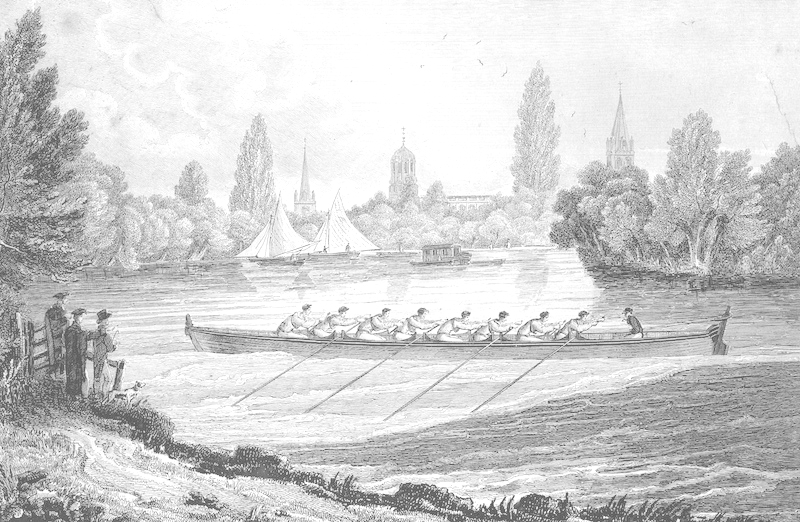

In the early days of Oxford college rowing, these two colleges were the only crews competing, and were joined shortly thereafter by Christ Church and Exeter. Students would row to the Inn at Sandford-on-Thames, a few miles south of Oxford, and race each other on the way back. The races started at Iffley Lock and finished at King’s Barge, off Christ Church Meadow. Flags hoisted on the barge would indicate the finishing order of the crews. Crews would set off one behind the other, the trailing boats trying to catch, or “bump”, the boat ahead. The bumped boat and the bumping boat would swap places the next day. The aim was to become the lead boat, known as Head of the River. For identification, crews wore college colours and emblazoned the rudder of the boat with the college coat of arms. John Middleton, the “Childe of Hale,” was a 17th-century giant, standing over nine feet tall, from Hale in Lancashire. He accompanied his landlord, Sir Gilbert Ireland, to the court of James I, where he took on the King’s champion wrestler and won. Sir Gilbert, later Lord of the Manor of Hale, was a member of Brasenose College at the time, and he brought Middleton to College on his return from court, where two life–size portraits were painted of him wearing his “London costume” – a fantastic outfit of red, purple and gold. When, in 1815, the students came to establish a Boat Club, it was this story and tradition that was used as inspiration. The Childe of Hale has since been a role model for generations of rowers and a portrait still hangs in the college. By tradition, the First VIII is always called “The Childe of Hale,” and the First VIII colours are those of the Childe’s London costume.

The Childe of Hale

John Middleton, the “Childe of Hale,” was a 17th-century giant, standing over nine feet tall, from Hale in Lancashire. He accompanied his landlord, Sir Gilbert Ireland, to the court of James I, where he took on the King’s champion wrestler and won. Sir Gilbert, later Lord of the Manor of Hale, was a member of Brasenose College at the time, and he brought Middleton to College on his return from court, where two life–size portraits were painted of him wearing his “London costume” – a fantastic outfit of red, purple and gold. When, in 1815, the students came to establish a Boat Club, it was this story and tradition that was used as inspiration. The Childe of Hale has since been a role model for generations of rowers and a portrait still hangs in the college. By tradition, the First VIII is always called “The Childe of Hale,” and the First VIII colours are those of the Childe’s London costume.

Walter Woodgate & the Coxless Four

In 1868, Woodgate sought to introduce rowing without a coxswain at Henley, in the style of the St. John’s, New Brunswick. This produced a protest from Mr Wood of University College in the form of a letter to the Stewards. He claimed that, while rowing without a coxswain was allowed by literal interpretation of the rules, the intention of the rules was that a coxswain should be carried.

Only days before the regatta, the Stewards passed a rule that coxswains must be carried. The Brasenose boat had no fifth seat for a cox, and was fitted with a wire and lever attached to a footplate for steering. Unable to change boat and style, or produce a practised steerer at such late notice, Brasenose had to choose between scratching or taking their chance of establishing their reputation for speed.

Woodgate wrote to the Stewards that he would comply with the decision regarding starting with a coxswain, but that the cox would jump overboard immediately after the start. For this reason, the trial heats for the Stewards’ Fours had been anticipated by many, and a large crowd gathered.

As soon as the umpire announced “go”, Frederic Wratherly plunged into the river, having been perched on the stern of the four, and after a narrow escape from strangulation by water lilies, swam to shore. Meanwhile, the four rapidly overhauled the two other crews and won by a hundred yards. The result didn’t stand, however, as the four was immediately disqualified. Five years later, the Stewards’ became an event for coxless fours.

A special Prize for four-oared crews without coxswains was offered at the regatta in 1869 when it was won by the Oxford Radleian Club and when Stewards’ became a coxless race in 1873, Woodgate “won his moral victory,” the Rowing Almanack later recalled. “Nothing but defeating a railway in an action at law could have given him so much pleasure.”